UPDATE 5/31/2019. This needs a correction, but I want to leave it intact below for the record. I have in the title above and the text below that the Nextera data is contaminated by FFS patient data. This is not correct. To preserve HSA tax advantages, many of the Nextera patients did not want to pay a subscription fee; as is somwhat common in other DPCs, these patients paid a flat individual visit charge instead of a subscription fee.

I fully described this process, but it may be misleading for me to identify these patients as “fee for service” patients. It would have been better to have identified them as “non-subscription patients”.

Even so, these patients pay in a very different way than the subscription model identified by AEG/WP and other DPC advocates as a key to DPC efficacy. Specifically, they face costs at every visit which, in comparison to a subscription model, discourage regular visits.

Interestingly, creating a significant marginal cost for each visit in this way actually brings this form of non-subscription practice into compliance within the intended medical economic goals for which HDHP/HSA plans were created— in precisely the way that a subscription plan, which puts a zero marginal cost on each visit, cannot.

Accordingly, it remains fair to conclude that the Nextera member data is contaminated in a way that makes it difficult to attribute any observed cost savings to subscription model (“DPC”) medicine.

The following paragraph begins the original post.

The basic premise of AEG/WP’s advocacy for direct primary care is succinctly stated in “Healthcare Innovations in Georgia: Two Recommendations” at page 24.

“Establishing a relationship with a doctor for a fixed monthly fee can induce and empower many patients to see their primary care physician regularly, which results in decreased healthcare expenses and reduced health insurance premiums for Georgia residents.” Accordingly, the report notes, “The direct primary care model requires members to establish a relationship with a primary care doctor that would cost a fixed monthly fee.”

So why did AEG/WP source their claim that direct primary care reduces downstream care costs to a Nextera sales brochure touting its experience with DigitalGlobe, a document that reports on downstream claims costs of a small group of Nextera members, a large number of whom paid per visit charges rather than a fixed monthly fee?

Because of certain complexities in the tax treatment of payments for medical care, Nextera had good reasons for this admitted departure from the “ideal” of direct primary care. In any case, Nextera’s own account reveals that many members of the group for which cost reductions were claimed, were not direct primary care patients as defined by the AEG/WP recommendations.

Because the group had significant numbers of both fixed fee members and fee for service members, it is logically impossible to say from the given data whether the fixed fee Nextera members experienced downstream cost reduction that were greater than, the same as, or worse than the fee for service Nextera members. So, while the study does suggest that Nextera clinics foster downstream care savings, it can not demonstrate that fixed-fee direct primary care has any benefit.

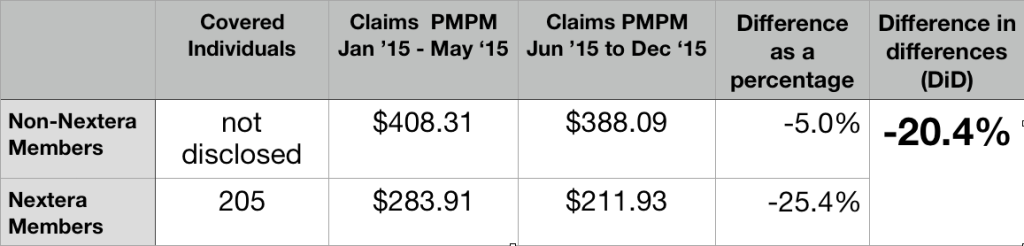

Here are the core data from the Nextera report.

205 selected Nextera; they had prior claim costs PMPM of $283.11; the others had prior claim costs PMPM of $408.31. This a huge selection effect. The group that selected Nextera had pre-Nextera claims that were over 30% lower than those declining Nextera.

Rather than award itself credit for that selection bias, Nextera relied on a “difference in differences” ( DiD) analysis. It credited itself, instead, for Nextera patients having claims costs decline during seven months of Nextera enrollment by a larger percentage basis (25.4%) than claim cost for their non-Nextera peers (5.0%), which works out to a difference in differences (DiD) of 20.4%.

What the data does not show is whether those who picked Nextera doctors and paid a fixed fee had any better downstream claims experience than those who picked Nextera doctors and paid on a fee for service basis.

The data presented in the Nextera brochure, in other words, do not isolate direct primary care status as the cause of the improvement. What the data show instead is the apparent effect, not of the “directness” of care but, of the “Nexterity” of care.

The principal conclusions of Nextera’s sales brochure, which the company styled a “case study”, are also tainted by errors of arithmetic.

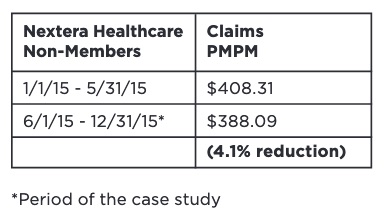

Here’s an image of a table clipped directly from their piece.

Do the arithmetic. The reduction rounds off to 5.0%, the number I used in the larger table above. Nextera’s ability to handle numbers is plainly suspect.

In the time since the report, Nextera has been actively claiming that its DigitalGlobe experience demonstrates that it can reduce claim costs by 25%. Nextera should certainly amend that number to the reflect the smaller difference in differences that its report actually shows. But even the substituted claim of 20% cost reduction would require significant qualification before that figure could be extended to other instances.

Even before they were Nextera members, those who were eventually enrolled seem to have been markedly low risk, lower I believe than any cohort previously identified in any of the literature addressing direct primary care. The Nextera population may be so much different from those who declined that the trend observed for the one DigitalGlobe population can not be assumed even for the other DigitalGlobe population, let alone for a large, unselected population like the entire insured population of Georgia.

Consider, for example, an important pair of clues from the Nextera report itself: first, Nextera noted that signup were lower than expected, in part because of many employees “hesitancy to move away from an existing physicians they were actively engaged with”; second, “A surprising number of participants did not have a primary care doctor at the time the DPC program was introduced”.

As further noted in the report, the latter group “began to receive the health-related care and attention they had avoided up until then.”

A glance at Medicare, reminds us that routine screening at the primary care level is uniquely cost-effective for beneficiaries who may previously avoided attending to their health. Medicare’s failure to cover regular routine physical examinations is notorious. But there is one reasonably complete physical examination that Medicare does cover: its “Welcome to Medicare” exam.

First attention to a population of “primary care naives” is a way to pick the lowest hanging fruit available to primary care. Far more of that fruit can be harvested from a population enriched with people who are receiving attention they have avoided than from a populations enriched with those who are already actively engaged with their existing physician.

Accordingly, the 20% difference in differences savings can not be automatically extended to the non-Nextera group.

Relatedly, the comparative pre-Nextera claim cost figure may reflect that the Nextera population had a disproportionately high percentage of children, of whom a large number will be “primary care naive” and similarly present a one-time only opportunity for significant returns to such preventative measures as a routine physical. But a disproportionately high number of children in the Nextera group means a diminished number of children in the remainder — and two groups that could not be expected to respond identically to Nextera’s particular brand of medicine.

A similar factor might have arisen from the unusual way in which Nextera recruited its enrollees. A group of DigitalGlobe employees with a prior relationship with some Nextera physicians first brought Nextera to DigitalGlobe’s attention and then apparently became part of the enrollee recruiting team. Because of their personalized relationship with particular co-workers and their families, the co-employee recruiters would have been able to identify good matches between the needs of specific potential enrollee needs and the capabilities of specific Nextera physicians. But this process would result in a population of non-Nextera enrollees that was less amenable to whatever was unique about Nextera. Again, no parallel trend could be assumed.

I am uncertain whether the results of these kinds of considerations would be deemed “selection bias” by a trained econometrician; I suspect they might be characterized instead as instances of “omitted variable bias”. However designated, these kinds of possibilities should be accounted for in any attempt to use the Nextera results to predict downstream cost reductions outcomes for a general, unselected population as envisioned by the AEG/WP authors.

Whether or not Nextera inadvertently recruited a population that made Nextera look good, that population was tiny.

Another basis for caution before taking Nextera’s 20% claim into any broader context is the limited amount of total experience reflected in the Nextera data. The report covered seven months experience for 205 Nextera patients. In fact, Nextera’s own report explains that before turning to Nextera, DigitalGlobe approached several large direct primary care companies (almost certainly including Qliance and Paladina Health); these larger companies declined to participate in a study so short for a group so small.

Total claims for the short period of the experiment were barely over $300,000, the 20% difference in difference claimed savings about $60,000. That’s a pittance.

Consider the two or three members who did not join Nextera in May 2015 because, no matter how many primary care visits they might want in the coming months, they knew they would hit their yearly out-of-pocket maximum and, therefore, not be any further out of pocket. Maybe one was planning a June maternity stay; another, a June scheduled knee replacement. A third was in hospital because of an automobile accident at the time for election. It is likely Nextera-abstention of these kinds contribute importantly to pre-Nextera claims cost differentials.

But the matter is raised here primarily to suggest the fragility of a purported post-Nextera savings of a mere $60,000 over seven months. An eighth month auto accident, knee replacement, or Caesarian could evaporate a huge share of such savings in a single day. The Nextera experience is too small to be reliable.

This seems a good juncture to note that Nextera has not chosen to present any downstream claims reduction experience more recent that 2015 — whether for DigitalGlobe or or any other group of Nextera patients. Perhaps Wilson Partners should have asked Nextera for data showing results for some of the forty-one months that intervened between the end of the initial seven month period and the time at which Wilson Partners addressed Nextera’s seemingly self-serving report .

Nextera now has over fifty doctors, a presence in seven different states, and patient numbers likely in thousands by now; it should have no problem generating newer, more complete, and more revealing data.

Because of its short duration and limited number of participants, because it has not been carried forward in time, because of the sharp and unexplained pre-Nextera claims rate differences between the Nextera group and the non-Nextera group, because the Nextera team makes patent errors of arithmetic, and because its cost reduction figures are contaminated by the inclusion of a significant number of fee for service patients, the Nextera study cannot be relied on as giving a reasonable account of the overall effectiveness of direct primary care in reducing care costs.