The “DPC is uniquely able to telemed” train has left the station. Everyone is telemeding now.

October 20, 2019: 500+ word Open Letter to Members of Congress by DPC Coaltion President asking for support and co-sponsorship of the The Primary Care Enhancement Act. Missing words: telehealth, telemedicine, virtual, telephone, phone, text message, text, SMS.

March 26, 2020: DPC Coalition laments exclusion of the bill from CARES despite being sold as “means of expanding virtual care to 23 million more Americans with HDHP/HSA plans.”

Fortunately, all 23 million HDHP members dodged that bullet when a huge swatch of FFS primary care docs (along with DPC docs willing to code) stepped up to virtual care practically overnight.

Have a look at this for example:

In literally a week we have had 50 providers convert to providing a virtual care model that includes phone-visits, e-messaging, and video visits. We’ve seen the mindset shift from considering what we might use telehealth for to what we can’t use telehealth for. In just one week we have transitioned 50 percent of our clinic visits to a virtual format.

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/qa-preparing-pandemic-rural-minnesota

It is likely that on a single day or two last week, (3/23 to 3/27) the number of FFS PCPs who learned to telemed exceeded the total number of DPC docs present in country. By April 1, there should be many fold more telemeding FFS docs than telemeding DPC docs. [Indeed, a U.S. Senator from Georgia bet on that a month ago, buying telemedicine-related stock based insider information about the impending disaster. ]

Marcus Welby had neither a subscription model nor a telemedicine app.

Pandemic effects on DPC enrollment

Possibilities to think about:

- DPC members who lose employer coverage will have the ability to go to ACA-compliant marketplace plans. Many of these will reach the low income levels at which ACA provides robust cost-sharing reduction is available. The relative desirability of DPC will fall.

- Some DPC members who lose income will become Medicaid eligible, especially in expansion states.

- Some states that have not done so yet will accept Medicaid expansion, reducing the number of those whose health plan was “DPC + hope.”

- A high percentage of DPC members have HDHP plans (technically illicit). HDHP plans have bigger advantages for higher income people. A general downward slide in income coupled to an opportunity to change plans if group coverage is lost due to job loss will likely see a shift out of HDHP plans. Even if those shifting don’t see incomes low enough for the robust cost sharing, they will have less incentive for DPC.

- Some DPC members will not be able to keep up their monthly payments. Some of them, especially those with relatively low utilization in the past, are going to be upset if they are discharged from the practice.

- More people will hit, or expect to hit, full amount of deductibles or MOOPs, reducing the relative value of DPC membership.

- For a while at least, there will be less “high-touch” medicine of any kind. This reduces the relative value of DPC subscription model.

More to some. Use comments to tell me of other issues.

Based on the above, I expect DPC clinic to lose subscribers this year. A DPC/HDHP fix, if part of Covid-stimulus, would have moved the needle somewhat toward more subscribers; it did not happen.

Direct Primary Care & COVID-19: some takes on Dr. White’s piece on dpcalliance.com

Update 4/22/2020. This one was mostly reactive to Dr White’s DPCAlliance.com essay on DPC and COVID-19. That was dated 3/19/20. I wrote this mostly in reaction to unseemly opportunism, not so much by White as by Flanagan and Springer as discussed. In retrospect, what DPC Coalition tried to do here looks almost pathetic. Expressly pitching DPC as a means of bringing telemedicine to 23 million HDHP/HSA plan members was lost in a tsunami of FFS primary care converting to telemedicine. In a follow-up piece, White admits he was wrong.

Two of the take-home lessons of the original version of this post are presented better in these briefer posts. A third is simply this: Nearly all of the fervently claimed advantages for DPC whether in a time of COVID or at any other time derive from panel size, not payment model.

I am keeping this post anyways, for context, reference, whatever.

I don’t think this a good moment for the usual coupling of disparagement of traditional practice with praise for DPC. The White article, which when published became the public face of DPC Alliance on the subject of COVID, does very little more than say , “OUR DPC patients and physicians are going to be fine; the other guys, not so much”

However, whether it be 24/7 telemedicine, emptier waiting rooms, faster response times, healthier patients more able to survive an infection, more personal knowledge whatever, isn’t every one of the cited advantages for DPC in a time of COVID equally held by FFS/concierge? Isn’t this about the panel size, not payment model?

If a pandemic mandates anything for doctors, it’s that each handle more patients, not fewer.

What about descending on Congress with a general pro-DPC agenda disguised as a crucial pandemic policy? I hope that isn’t what’s going on. But there’s more than hint of that in some quarters. One of the first DPC practictioners replied to a tweet of Dr White’s essay suggesting just that. And a recognized leader of the DPC community, chimed in, ” It’s already happening.” Here’s the tweet, the reply, and the chime in.

Are DPC’s lobbying crew going all in on the idea that DPC is a “proven solution” — for COVID? That making DPC happen now for more patients is a COVID strategy?

Springer: “I’ve spent two days doing virtual visits to which I was largely unaccustomed; let’s tell Congress that’s a COVID plan that only DPC can do.”

Then there’s this from another group of DPC activists: https://dpcaction.com/never-let-a-crisis-go-to-waste. In which they (DPC Action) urge that “during this time of National Emergency” Congress must pass their favorite DPC/HDHP fix.

While a DPC/HDHP fix might be justified, pandemic surge needs are not that justification.

I won’t, as such, have any objection to the principle of attaching DPC/HDHP fix legislation to any other legislation that’s moving, unless something more important in COVID-19 Package #3 is taken as a hostage to getting a DPC/HDHP fix.

Still —

A DPC/HDHP fix should rise or fall on its own merits, which may have little to do with pandemic policy going forward.

A boost to telemedicine should rise or fall on its own merits, which may have a lot to do with pandemic policy going forward.

Boosting access by lowering cost sharing should rise or fall on its own merits, which may have a lot to do pandemic policy going forward.

Pandemic COVIDcare going forward now seems likely to be optimized by”telemedicine” and “lowered cost sharing” at least at the diagnosis and early treatment stage. But these can be achieved in FFS settings, as being shown in real time at hint.com by actual DPC leaders actively recruiting actual DPC docs for FFS-based telemedicine. Arguments for surge-telemedicine are arguments for surge-telemedicine, and are best met by legislation that promotes surge-telemedicine. Surge-based arguments for low cost sharing are surge-based arguments for low cost sharing, and are best met by lowering cost-sharing where this helps deal with the surge. COVID related legislation has already moved these needles and will likely do so to an even greater extent. Telemedicine and cost barrier removal can be and is being facilitated in a very big way directly for everyone (insured, public supported, uninsured) through DPC, FFS, or other practices, for the duration of COVID-need (or even for freaking ever), all at the snap of a handful of federal and state government fingers.

Once the pandemic/public health case is made for boosting access by lowering cost sharing and practicing telemedicine, and such efforts properly funded, there’s no public health/pandemic rationale for a DPC/HDHP fix for DPC monthly fees.

At the same time, that kind of fix for DPC monthly fees is (a) limited to only those for whom HDHP plans are otherwise worthwhile and (b), even then, is only a roundabout way to upscale telemedicine and lower-cost sharing for pandemic services. In DPC, freedom from usage based cost- sharing must be purchased with monthly and even initiation fees, fees that can in themselves might act as barriers to care. But from a pandemic/surge perspective, it makes more sense to just exempt COVIDcare from usage-based cost-sharing so that, even in FFS medicine, COVIDcare goes forward. Some states have already mandated this, even for those in HDHP plans. Again, from a pandemic perspective, why try to drive HDHP plan members toward desirable telemedical care by the indirect route of offering a tax-break, useful only by some and then in varying degrees, in the hopes that some of those some will buy subscriptions for DPC? Instead, telemedicine by FFS, DPC, or anyone else can be directly facilitated as part of cost-sharing-free COVID care, by direct subsidy, by relaxation of any restrictions, whatever.

Accordingly, whether or not a DPC/HDHP fix might be justified for other reasons, no cautious policy maker would consider pandemic surge needs a significant argument for a fix; and no reasonable policy maker would let pandemic surge needs be held hostage to a DPC/HDHP fix.

White’s piece repeatedly and primarily stresses small DPC patient panels. This is an odd thing to emphasize at a moment when what the crisis is likely to produce is a community need to have all hands on deck for relatively brief interactions with relatively very large numbers of patients.

Which do you think will save more lives next Monday: 33 ten minute focused COVID-related encounters or 11 thirty minute encounters? The ten-minute visit, usually scorned by everyone, could well be just the thing here in late March of 2020.

I would far rather have seen a DPC Alliance article that said: “We have small patient panels and we usually focus on their long-term care goals; in the current context, that luxury needs tempering in the face of community need; fortunately, Congress and has passed emergency legislation which will allow us to accept uninsured patients for COVID-19 screening and appropriate primary care; we eagerly embrace that opportunity.” As noted both above and below, some DPC have chosen to do that.

At its best point, White’s article hails telemedicine. But even that useful bit is tainted with White’s apparent belief that DPC necessarily does telemedicine better than anyone else. Still, at least White acknowledges that other forms of practice do have telemedicine capability; over at Twitter, White’s article is re-tweeted with favorable comments by DPC-friendlies who seem to write as if DPC has a monopoly on telemedicine. (Ironic, considering that one of the first tweet responses to White’s piece was the one shown above, from a DPC doc who made clear that he had just just gone a year without a significant number of virutal visits.)

I have some familiarity with the dominant large health systems in three major cities . Despite “FFS”, the large players there have robust, sophisticated, effective patient portal systems.

And every day in this middle of March 2020, we are seeing wide-scale “tele-operations” being successfully implement by schools, businesses, religious institutions, etc. In a political campaign nearly ten years ago, I learned first hand how a small group of co-workers could conjure up major telecom initiatives on the fly with a few simple software tools, net access, some lap tops and cell phones.

Certainly COVID may at some point overwhelm these systems by sheer volume. That’s not a fault in FFS-based medicine and it will not reveal a unique virtue of DPC. To the extent that individual DPC practices do not become overwhelmed, it will be because of small panel sizes, i.e., they will be doing no better than an FFS based concierge practices and doing that well for largely the same reason – small panel size. Not payment model, just small panel.

Who thinks there should be an HDHP fix for concierge fees?

And, more specifically in response to the White essay, none of DPC’s presumed advantages in a time of COVID flow from the payment model. Whether it be 24/7 telemedicine, emptier waiting rooms, healthier patients more able to survive an infection, whatever, every one of the cited advantages for DPC in a time of COVID is equally held by FFS/concierge; it’s about the panel size, not the payment model.

The more highly staffed any system is, the more headroom it will have before it break under pandemic stress. But the payment model by itself does not determine the staffing level. A far more important determinant, for example, are physician expectations of what they should be paid.

Granted, squeezing out insurance related overhead presents a good opportunity to buy some more physician bang for the medical buck. But, as I discuss elsewhere in this blog, it has yet to be shown DPC is generating the huge savings so often promised. Nextera Healthcare, mentioned above, is sometimes included as a poster child for effective DPC; but its own, current, publicly available marketing material claims overall net savings of less than 15%. That’s marginal, not revolutionary.

And even that data and analysis lacks rigorous vetting by independent professionals.

Moreover, that data compares Nextera to FFS primary care in the context of employer health plans. If the benchmark here is who can do better in the recently created Congressional COVID care for the uninsured, or in supplementing stressed networks by a streamlined telemedicine program at the diagnosis stage, that kind of work will likely have modest administrative costs. Coding geniuses will not be required, or even useful.

And that’s precisely why “Hint” is comfortable being all over the intiative mentioned bth above and below: FFS telemedicine for DPC doctors.

Department of Credit Where Credit Is Due

Better late than never, this is what DPC Alliance lead post on COVID should have been about:

In a conference call 800PM EST 3/19/20 organized by hint.com, its leadership announced an intiative to put lots of DPC’s MDs to work doing telemedicine when and where needed. They’ll hook docs up to reach into communities whereever needed. There are emergency licensing arrangements to facilitate.

Now cue the Department of Irony. This work will involve even working hand in hand with FFS-tainted entities, coding , and submitting claims for governmentally supported third-party payments.

This seems, for now, exactly what’s needed from DPC docs. Not a payment model; not 30 minute face-to-visits. And making it happen did not depend, at all, on a DPC/HDHP fix.

Dr Priceline’s downstream cost reduction plan cannot simply be scaled up.

Dr. Lee Gross of Epiphany, a direct primary care leader, brags about the great discounts he gets for his patients on downstream procedures like advanced radiology. And, specifically, he proudly lets us know that a big part of this involves accessing advanced equipment during slack hours. This is, of course, the same strategy by which discounters like Priceline are able to book last minute hotel rooms at big discounts.

As long as marginal costs of production are met, vendors are happy with discounts for inventory that would otherwise become unsalable. But, Dr. Gross, the total of all sales prices has to exceeed the total of all costs of production; else there is no profit. Discount after-hours bookings for MRIs will be available at, and only at, the margins.

The broader world of downstream care pricing will not likely be remade by direct primary care practices applying Dr. Gross’s Pricelining technique. If there is any real value to be extracted by, for example, off-peak MRI scheduling, health insurers and large provider systems will be better equipped to exploit that opportunity than direct primary care clinicians who choose to sacrifice face time with their patients to spend telephone time as downstream care brokers.

Come to think of it, is there any legitimate reason for direct primary care physicians — who pride themselves on long, probing patient visits — to spend their precious time acting as downstream care brokers? How exactly has the DPC MD who delivers meds to your office, or opens her surgery for a Sunday meds pickup become a symbol of cost-effective care?

Doctor Gross plainly understands that a seller of MRI services is willing to provide lower cost services at below average prices so long as marginal costs are met. But many of his compatriots describe accepting Medicare and Medicaid patients at payments lower than average fees as “losing money”, even when that amount of price discrimination can add to a practice’s bottom line. And I don’t hear them grousing about how Gross’s patients are not paying their fair share of MRI costs, even as I hear them make the equivalent complaint about Medicare and Medicaid patients.

I actually hope that many doctors who have engaged in policy advocacy were blinded by ideology, or simply lying.

I see so much bad analysis and arithmetic in policy advocacy by MDs, I have to hope that it’s a result of ideological blind spots, or even outright lying. I am frightened by the principal alternative explanation: that one can too easily become an MD despite the lack of basic analytical or arithmetic skills.

Making cost reduction claims more honest and helpful to decision-makers — random thoughts.

Claims of cost reductions need to look comprehensively at all costs.

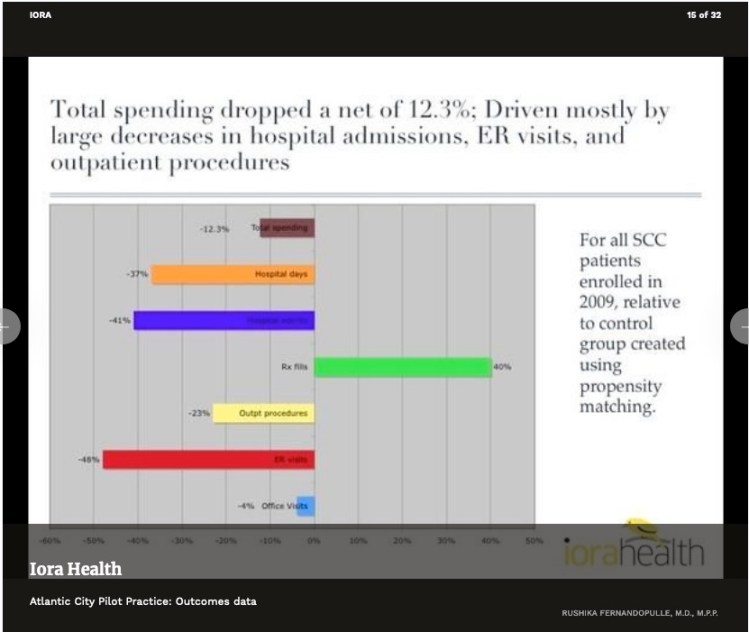

Consider this chart from an Iora presentation of some years ago.

The net drop in spending would look a lot bigger if prescription drugs (the green bar) were not part of the picture. But, a lot of how primary care, direct or otherwise, works is by getting people on the right meds, then getting them fully compliant. When you spend money to save money, you need to look at a net change.

Perhaps the most widely cited claim of cost reductions is Qliance’s 2015 press release claiming overall reductions of about 20%. But their analysis did not cover drug costs. It seems highly probably that somewhat higher drug costs for Qliance’s is a major driver of the reductions in other categories of care. In that case, their overall cost reduction is probably significantly below the 20% they claimed. (And, lest we forget, the Qliance data made no attempt to examine the possibility of selection bias.)

Similarly, consider that Qliance’s 2015 data omitted a category that had been included in their own earlier internal analysis, specifically, surgeries. Qliance’s 2015 evaluation of “overall costs” did not include surgeries. If Qliance patients had just as many surgeries as non-Qliance patients, incorporating that result would lower overall savings. And, just as the case with prescription drugs, there’s some chance that Qliance’s success in reducing other costs might even come from its patients having more surgeries.

So, to generalize, a proper demonstration of success at overall downstream care cost reduction needs to consider all downstream costs to fairly reflect the achievement of direct primary. Cherry-picking of selected reported categories that show improvement gives a misleading picture. Several studies have, to their credit, used comprehensive measures of all downstream cost.

Ideally, studies are repeated at a fair interval or extended for an ample single period. A single snapshot or short-term study, if high or low, will likely regress to the mean when repeated or extended.

A study of a single start-up period may be distorted. It may take more time for the full effect of DPC to develop its full value. On the other hand, there is good reason to expect that a start-up period will pull in a disproportionate share of enrollees who have never had an prior primary, in which case there might be a first year bonus of discovered problems.

Claims about the efficacy of direct primary care providers have a lot more credibility when they report data from direct primary care providers and not from concierge practices. MDVIP is not a direct primary provider and neither is White Glove Health. Yet, they have appeared in pro-DPC advocacy repeatedly.

Study by bona fide independent investigators is much preferred to self-reported brags, for the simple reason that self-studies that don’t favor the self-student are buried. Ultimately, the studies that best show real success are the studies that are designed to show the truth, whether that be success or failure.

DPC and Medicaid expansion politics.

DPC docs uniformly recommend that their non-indigent patients have wrap-around insurance coverage. But for indigents, particularly for what are known as “Medicaid expansion adults” too many DPC docs are willing to push their state for an indigents’ program heavy on direct primary care coupled to, at best, skimpy coverage of downstream costs. They’re eager for their states to send a windfall their way, and apparently quite willing to provide ammunition for fiscal conservatives whose only real goal is spending as little as possible on indigent care.

Peer-reviewed research has confirmed that full Medicaid expansion has significant health benefits for its beneficiaries. For DPC providers to fuel the opposition to full Medicaid expansion by supporting “DPC+ (too little)” is not a good look.

DPC providers would do well to look at this through the eyes of an indigent beneficiary given a choice between full Medicaid expansion (even if, heaven forfend, it comes with FFS primary care) and whatever flavor of “DPC+chintz” they are asked to get behind.

At least DPC advocates should think their own interests through quite thoroughly. Those militant cost-cutters always find a way to cut indigent care; they are the folks who have always made sure that Medicaid reimbursement rates be meager. If DPC actually was so effective that a “DPC + chintz” plan resulted in the indigents getting anything resembling comparable care to the non-indigent, after a year or two fiscal conservatives will complain that “the poor don’t deserve care as good as everyone else’s”, and cut to a meager level the amount they pay DPC providers .

A moment of clarity about selection bias – at a DPC summit.

At 2019 Summit, Mike Tuggy, MD, FAAFP, presented this: What Have Primary Care Practices Provided to Employers Who Invested in Primary Care? The Results Speak for Themselves–Reports from Across the U.S.

His presentation began with high praise for Qliance and others. He suggested that these models might be used to entice employers into a DPC experiment. Strikingly, he did not mention selection bias or risk adjustment in connection with using these data sources to entice employers to sign up. Certainly, there was no acknowledgement that one of his poster-children, Nextera, had a very low-risk membership.

Even more strikingly, however, the talk ended up in a Q & A that focused heavily on (a) the problem of having too many high usage patients as members, and (b) being certain that potential employer contracts compensated the DPC better for riskier patients. It even reached the point of a benefits broker offering the equivalent of underwriting services for DPC clinicians.

It’s good to see some realism about selection issues deployed when it helps DPC providers . It would also be appropriate to bring some when realism about selection bias that might be lurking behind claims of DPC success.