Advocates for the DPC movement have many stories to tell the public about how great DPC is. Some of their most potent narratives, however, are as misleading as their slew of quantitative studies. One root cause is that DPC advocates seem unable to imagine anyone else being as clever as they are.

The ur-brag of all of DPC is the preventative value of barrier-free primary care visits. Let us mostly put aside that many DPC clinics all but beg their patients to choose high deductible plans out of one side of their mouths, while they use the other side to decry the effect of high deductibles on primary care. And let’s put aside that for those with no insurance, the high price of DPC monthly fees is its own barrier to care.

There’s still this. The numbers of third-party insurers, individual and employer, that have figured out the virtue of low barrier primary care is very, very large.

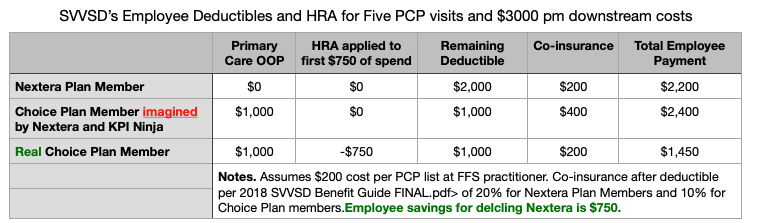

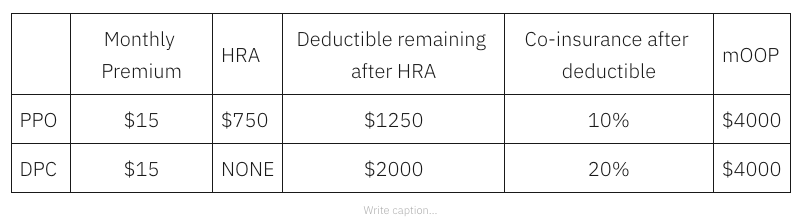

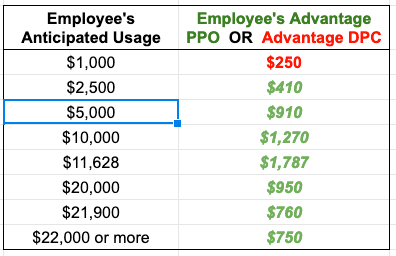

The vast majority of employer plans make primary care visits pre-deductible. Yes, there are copays – almost always modest, especially given that employer plans go to people with real jobs who can, therefore, afford reasonable co-payments. Then, too, many employers have HRAs that meet hundreds of dollars of deductibles, typically starting with the first dollar.

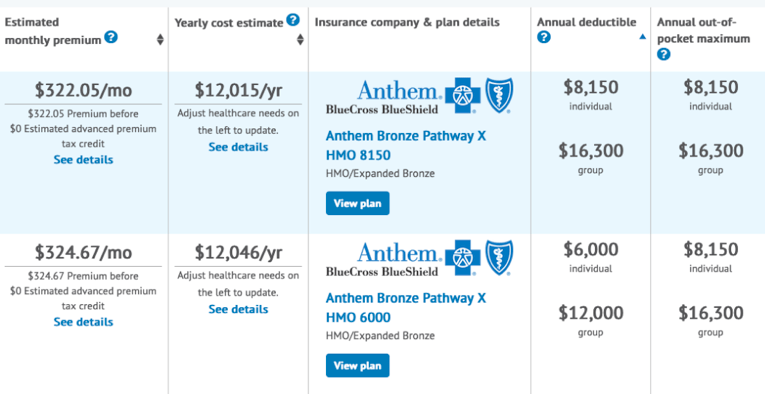

Then, look at the individual market. In the ACA individual market, cost-sharing reductions bring copay, deductibles, and mOOP down to trivial sums for those with incomes up to 200% FPL. And for those with higher incomes, many plans with even very high deductibles come with pre-deductible primary care visits. Even ACA catastrophic plans come, by law, with three pre-deductible primary care visits.

Many of the most important preventative services are covered without cost-sharing for nearly all insureds, But, because DPCPs do not make insurance claims, DPC patients often end up paying for them. A proud DPC subscriber recently tweeted, with joyful amazement, that the only part of her pap test for which she had to pay was pathologist’s interpretation; that part would have been free with her insurance.

A recent self-brag by an employer-option DPC shed crocodile tears over the health risks to the 6.9% of non-DPC members who “received no care at all” in a particular study year, so adjudicated because they had no filed claims during the period. A few pages earlier, the same study bragged about all the phone calls the DPC provider took on matters like prescription refills or quickly advising patients on what to do about a fever or sprain. Does it never occur to DPC advocates that non-DPC patients with trusted FFS-PCPs often dispose of similar matters similarly? Have they never seen patient portals? Have they not heard that large medical systems (and insurers) have 24/7 triage nurses of whom you can make inquiries about fevers and sprains without charge? Do they not remember that one of the historical reasons PCPs turned to the subscription model was so that they could get paid for traditionally un-billed services like routine prescription renewal or telephone triage for fever and ankle sprains?**

The average person in the country has about 1.5 primary care visits a year. 6.9% of them managing a given year with no visits is quite expectable. Absent evidence correlating health outcomes with higher frequency primary care visits, the quite expectable is also the quite acceptable.

One particular DPC advocate keeps repeating that, “a primary purpose of direct primary care is to prevent a claim from happening in the first place.” To the extent that he is saying that DPC docs with an eye on business development will go far to keep their downstream utilization stats looking good, he’s probably right. That’s not necessarily a good thing.

On the other hand, to the extent he is suggesting that FFS-PCPs do not think about how to keep their patients from needing downstream care, that’s profoundly insulting.

One pet theme of most D-PCPs is “Who can better determine quality better than my patient?”; this is invariably coupled to a claim about that D-PCPs high patient retention rate.

And yet, in the Milliman report on the Union County employee DPC clinic, the actuaries observed a huge risk selection bias against the DPC. The given explanation: sicker patients preferred sticking with their established PCP rather than being forced to accept one of a small number of clinic doctors. To my mind, this seems to evidence that access to a larger community of fee for service doctors produces quality care: who can better determine quality than this chronically ill patients who turned down DPC clinics?

A favorite DPC advocate argument is, “Insurance is for big things. You insure your car for accidents but not for oil changes.” But there is a flip side. I do not have a primary car care subscription plan with the garage that does my oil change/maintenance checks, tuneups, and routine small repairs. So why are DPC docs selling insurance against colds and office based procedures like suturing and foreign body removal? (Yeah, I know, “DPC isn’t insurance. Yadda. Yadda.”)

DPC advocates brag that their frequent long visits result in their catching problems early. Even putting aside the lack of hard evidence that DPC practices actually do “catch it earlier”, are DPC advocates really unaware that plenty of FFS doctors catch plenty of conditions early? That the very phrase “caught it early” is vastly older than DPC? Most specifically, does every DPC doc deny ever having “caught it early” when they were in earlier FFS gigs or in their current FFS side gigs?

** Just a few years back, distant from home, but where I had a few friends and family, I once arrived a bit unwell and without medicine, but nothing emergent. About an hour after I arrived, I got a call from a local FFS practitioner. “Hi, I’m Doc X, a friend of Bob S. Bob thinks you may need a ‘script or something. What’s going on?”