Skillful actuarial work on risk adjustment. A clear warning against relying on studies that ignored risk adjustment. Clear repudiation of a decade of unfounded brags.

An admirable idea on “isolating the impact of DPC model” from the specific decisions of a studied employer.

Milliman should have recognized that the health service resources that go into providing direct primary are vastly more than the $8 PMPM that emerged from its modeling and should have done more to subject the data on which the number rested to some kind of validation.

Upshot: there is still no solid evidence that direct primary care results in a reduced overall level of utilization of health care services. Milliman’s reporting needs to clearly reflect that.

Overview: A core truth, and a consequence.

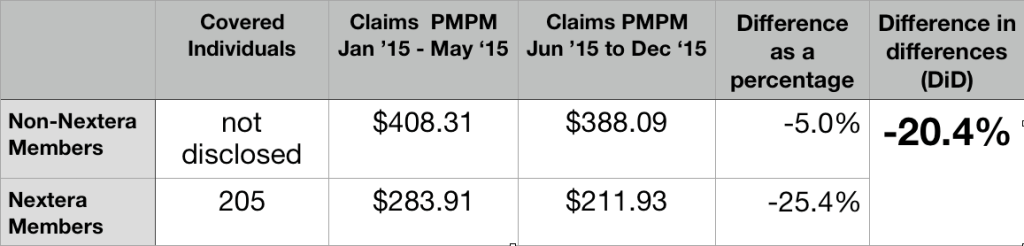

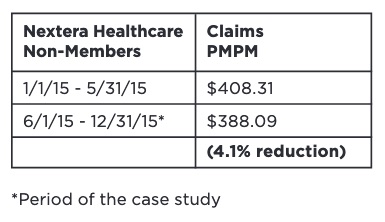

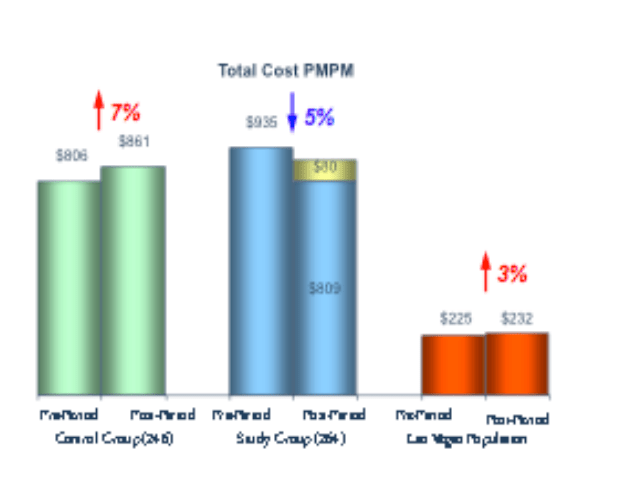

The Milliman report on the direct primary care option in Union County has significant truth, an interesting but unperfected idea, and staggering error. The core truth lay in Milliman determining through standard actuarial risk adjustment that huge selection effects, rather than the wonders of direct primary care, accounted for a 8.3% difference in total health care costs between DPC and FFS populations. Both Union County and the DPC provider known as Paladina Health had publicly and loudly touted cost differences of up to 28% overall as proof that DPC can save employers money. But naysayers, including me, were proven fully correct about Union County — and about a raft of other DPC boasts that lacked risk adjustment, like those regarding Qliance.1

The estimated selection pattern in our case study emphasizes the need for any analysis of cost and utilization outcomes for DPC programs to account for the health status and demographics of the DPC population relative to a control group or benchmark population. Without appropriate consideration for how differences in underlying health status affect observed claim costs and utilization patterns, analyses could attribute certain outcomes to DPC inappropriately. We urge readers to use caution when reviewing analyses of DPC outcomes that do not explicitly account for differences in population demographics and health status and do not make use of appropriate methodologies

Page 46 of Milliman/Union County study

Still, Union County had made some choices in regard to cost sharing that made some results seem less favorable for DPC than they needed to be. That’s where Milliman’s ingenuity came into play in what might be seen as an attempt to turn the County’s lemon into lemonade for the direct primary care industry. And that is where Milliman failed in two a major ways more than important enough to make the lemonade deeply unpalatable.

The Union County DPC program was even more of a lemon than Milliman reported.

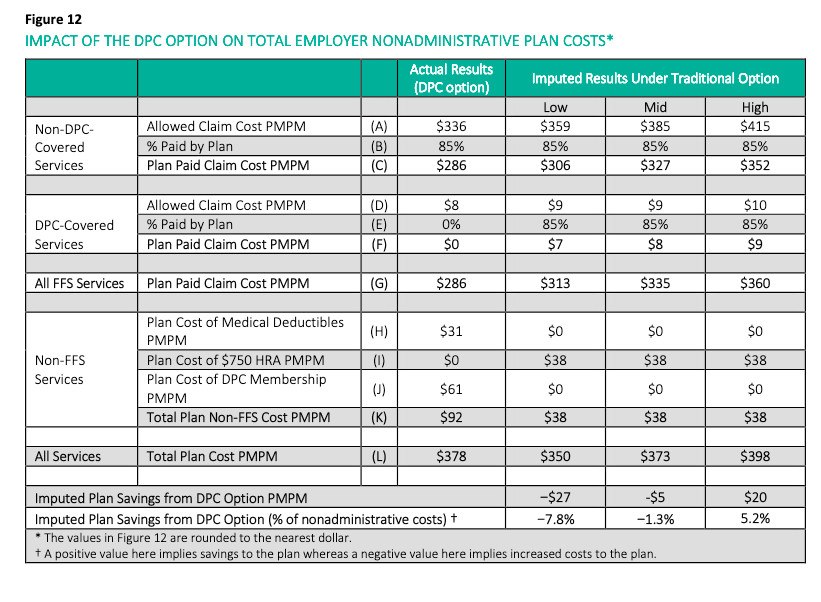

To the Milliman team’s credit, they did manage to reach and announce the inescapable conclusion that Union County had increased its overall health care expenditure by implementing the direct primary care option. Even then, however, Milliman vastly understated the actual loss. That’s because its employer ROI calculation rested on an estimate of $61 as the average monthly direct primary care fee paid by Union County to Paladina Health; the actual average month fee paid was $106. There had been no need for a monthly fee estimate as the actual fees were a matter of public record.

Though $1.25 million in annual savings had been claimed, the total annual loss by Union County was over $400,000. Though 28% savings had once been bragged, the County’s actual ROI was about negative 10%. Milliman’s reliance on an estimate of the fees received from the County, rather than the actual fees collected, made a fiscal disaster appear to be close to a break even proposition.

Milliman’s choice likely spared the county’s executive from some embarrassment.

For more detail on Union County’s negative ROI and Milliman’s understatements of it, click here and/or here.

The Milliman team came up with an interesting idea, but their thinking was incomplete and they flubbed the execution.

To prevent the County’s specific choices about cost-sharing from biasing impressions of the DPC model, Milliman developed a second approach that entailed looking only at a claim cost comparison between the two groups. According to Milliman, “this cost comparison attempts to isolate the impact of the DPC delivery model on the overall level of demand for health care services“. [Italics in original].

The Milliman calculation of 12.6% overall savings turns on a a massive underestimate of the cost of the direct primary clinic studied.

Milliman needed to determine utilization for the DPC clinic.

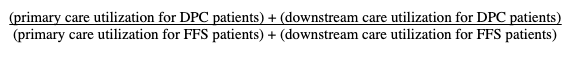

Milliman’s model for relative utilization is simple:

Milliman used claim costs for both downstream components of the computation, and for the FFS primary care utilization. But because DPC is paid for by a subscription fee, primary care utilization for the DPC patients cannot be determined from actual claims costs.

One reasonable way of estimating the health services used by DPC patients might be to use the market price of DPC subscriptions, about $61 PMPM. With this market value, the computation would have yielded a net utilization increase (i.e., increased costs) for DPC. Milliman eschewed that method.

Another reasonable way of estimating the health services used by DPC might be to estimate the costs of staffing and running a DPC clinic. Using readily available data about PCP salaries and primary care office overhead, estimated conservatively this would come to at least $40 PMPM. Had it sued that figure, Milliman would have been obliged to cut its estimate of savings by more than half.

The lower the value used for utilization of direct primary care services, the more favorable DPC appears. Ignoring models that would have pointed to $61 and $40 values, Milliman used a methodology that produced an $ 8 PMPM as the value of the resources required to provide direct primary care. This resulted in a computed 12.6% reduction in overall usage.

But $8 PMPM is an absurdly low value. Just try asking a few DPC providers what they would give you for eight dollars a month. Most will – rightly – regard it as an insult. Their usual charge for adult care is usually about 8 to 10 fold higher than that.

Milliman’s “ghost claims” method was ill-suited for DPC and vulnerable.

Milliman’s “solution”, however, turned on the stunning assumption that utilization of subscription-based holistic, integrative direct primary care could be accurately modeled using the same billing and coding technology used in fee for service medicine.

As a group, the DPC community loudly disparages such coding for failing to compensate most of the things they do to improve overall care, such as slack scheduling to permit long, same day visits. For another example, in the time frame studied by Milliman, there was no code for billing non-facing patient care coordination.

Examination of billing codes for downstream services is fully capable of harvesting the contributions the DPC plan may have made to reducing the health care resources used for downstream care. But owing to the lack of billing codes for the access and service level enhancements that characterize DPC, a billing code based model was largely incapable of capturing a significant share of the increased health care resources expended in delivering direct primary care.

Consider also that, D-PCPs consider coding for billing a waste of time and do not ordinarily use use billing friendly EHRs.

Yet Milliman chose to rely on the clinic’s unwilling DPC physicians to have accurately coded all services delivered to patients, then used those codes to prepare “ghost claims” resembling those used for FFS payment adjudication, and then to have submitted the ghost claims to the employer’s TPA, not to prompt payment, but solely for reporting purposes. The collected ghost claims were turned into the direct primary care services utilization by application of the Union County FFS fee schedule. The result was $8 PMPM.

The $8 PMPM level of clinic utilization determined by the ghost claims was absurd.

Valuing the health services utilization for patients at the direct primary care clinic at a mere $8 PMPM is at war with a host of things that Milliman knew or should have known about the particular clinic it studied, knew or should have known about the costs of primary care, and knew or should have known about the nature of direct primary care. Clinic patients were reportedly receiving three visits a year; this requires more than $8PMPM ($96 PMPY). The length of clinic visits was stressed. County and clinic brag 24/7 access and same day appointments for 1000 clinic patients. The clinic was staffed at one PCP to 500 members; at $96 a year, clinic revenue would have been $48,000 per PCP. This does not pass the sniff test.

The most visible path to Milliman’s $8 PMPM figure for health services demand for the delivery of direct primary care is that the direct primary care physicians ghost claims were consistently underreported. About what one might expect from “ghost claims” prepared by code-hating D-PCPs with no motivation to accurately code or claim (or, perhaps, even with an opposite motivation). Milliman even knew that the coding habits of the DPC practitioners were inconsistent, in that the ghost claims sometimes contained diagnosis codes and sometimes did not. Report at page 56.

Yet, Milliman did nothing to validate the “ghost claims”.

Because the $8 PMPM is far too low, the 12.6% overall reduction figure is far too high. As noted above, substituting even a conservative estimate of the costs of putting a PCP into the field slashes 12.6% to something like 4%. If in place of the $8 PMPM , the $61 market price determined in the survey portion of the Milliman study is used, Milliman’s model would show that direct primary care increases the overall utilization of health services.

For more detail on the “ghost claims” and erroneous primary care data fed to Milliman’s isolation model, click here.

Union County paid $95 a month to have Paladina meet an average member’s demand for primary health care services. That Milliman computed the health care services demanded in providing DPC to be $8 per month is absurd.

Milliman should amend this study by adapting a credible method for estimating the level of health services utilized in delivering primary care at the DPC clinic.

Milliman’s good work on risk adjustment still warrants applause. Indeed, precisely because the risk adjustment piece was so important, the faulty work on utilization should be corrected, lest bad work tar good, and good work lend credibilty to bad work.

1 The reaction to Milliman’s making clear the necessity of risk adjustment by those who had long promoted the Qliance boasts was swift and predictable: DPC advocates never ignore what can be lied about and spun. DPC Coalition is a lobbying organization co-founded by Qliance; a co-founder of Qliance is currently president of DPC Coalition. DPC Coalition promptly held a legislative strategy briefing on the Milliman study at which the Executive Director ended the meeting by declaring that the Milliman study had validated the Qliance data.